Kaitlyn: Just Getting Started

Kaitlyn was eleven years old when she stumbled upon a book I was reading. She brought it to me and, as if she had just discovered a brand new planet, she exclaimed with a sparkle in her voice, “Mom, these kids are like me!” My heart skipped a beat— she was obviously ready to learn that the children in the book, like her, were born with Down syndrome.

I am very pleased that she has the cognitive ability to recognize that she is different from other people, just as she recognizes, and perhaps has a better perspective than most people, that we are all different, special, and unique. How incredible it is that she knows what chromosomes are; that she has an extra twenty-first chromosome, which makes her similar to other people who have that same extra chromosome; and that it really isn’t all that different from the chromosomes that make some people red-haired like her sister, Jenni, or some people really big, like Shaquille O’Neal. How wonderful it is that she has the capability to process what Down syndrome means, and that she can rise above the usual expectations, despite the fact that she didn’t start off being a “high-functioning” child with Down syndrome. Kaitlyn certainly had a very slow start and didn’t really begin to change her course until she was almost ten and started on an NACD program. Today Kaitlyn definitely has already achieved far more than what traditionally is expected of people with Down syndrome, and she is just really getting started.

Kaitlyn, now 23, is happy, beautiful, gregarious, lights up a room, and is in a great relationship with a boy she adores. She is largely independent, keeping a busy schedule on a college campus, interacting with typical young adults, auditing classes, and doing research at the university library. She also volunteers at a day care center for at-risk children, manages time and money on her own, purchases her own meals, and speaks to groups about swimming (her favorite sport) and Down syndrome. We couldn’t have reached this point had I not determined early on that as her mother, I was to also be Kaitlyn’s advocate and cheerleader.

Although Kaitlyn was born at full term, she was tiny when she emerged into the world, weighing just 4 pounds, 4 ounces. Nothing during my pregnancy had indicated something might be “different” with my baby. My friend and I were so thrilled to be expecting almost at the same time. As we frequently rode the bus together, we talked incessantly about the babies: what we would name them, what cute clothes they would wear, and what furniture we were buying for the nurseries. We chatted about work arrangements and we dreamed--dreamed of being moms and excitedly anticipated the births of our first children. Then, in the blink of an eye, the eagerness transformed into shock at her delivery, when she was immediately whisked away to the NICU where she was to spend the next two weeks. The shock quickly turned into total acceptance of my precious baby girl with her fuzzy blond hair and lovely dark blue eyes, who also happened to have Down syndrome. She was beautiful and she was mine. It was about six hours from the moment I knew Kaitlyn had DS to when a clear, undeniable thought entered my mind: Kaitlyn was mine, and I was responsible for her growth and development.

From then on everything I did reflected that responsibility. At the end of my maternity leave, I quit my job to dedicate my attention to my first child. I shuttled Kaitlyn from doctor’s appointment to doctor’s appointment and from therapy to therapy, all the while feeling frustrated that I couldn’t do more and that the “therapy” was designed more to make me feel like something was being done, than to really help her. At the time I wondered if the lack of real meaningful help and therapy was a reflection of the services available in Scotland, where we were living; but after returning to the States I learned that it wasn’t any different. I felt like we were just spinning our wheels.

Like many children with Down syndrome, Kaitlyn had significant health issues. She had an atrial septal defect, which needed to be monitored closely. (Fortunately the hole in her heart closed on its own by the time she was eight.) Because she was so little at birth, she struggled to breastfeed, and eventually I had to switch her to a bottle. She suffered from relentless congestion, mouth breathing, and ear infections, which made it essential to have surgery to place tubes in her ears. I so wish I had known then what I know now from NACD about the problems associated with dairy products and the effects on mucus production, breathing, balance, hearing, receptive language, expressive language, and speech.

By the time she was three, Kaitlyn was still only babbling and had no intelligible speech. Her speech therapist wanted us to begin teaching her sign language. I disagreed. In my heart, I just knew that teaching her sign language would take her in the wrong direction and only further impede her speech. I insisted that the ST continue working on Kaitlyn’s speech. After all, she was trying to speak—she babbled all the time; we just didn’t know what she was saying. She needed to be motivated to find a way to organize her words and to improve her articulation, not stop her from trying and further separate her from the rest of the world. I believed that just because the speech therapist didn’t know how to teach her to talk, it didn’t mean Kaitlyn couldn’t learn to talk.

At three Kaitlyn didn’t walk, and she had never learned to crawl; instead she bum-shuffled across the floor. I wish I had known then what I later learned from NACD about how important it was for her to go through the normal developmental steps and why we should have discouraged the scooting and encouraged the basic developmental sequence of crawling and creeping, to not only teach her to walk, but to push her cognitive and language development as well. She did ultimately walk after her fourth birthday, but not well.

When Kaitlyn turned five I faced significant resistance from school administrators and other parents when I requested that Kaitlyn be placed in a regular class with typical children. I had to stand my ground and not let the opinions of the “experts” change what I knew in my heart was best for my daughter. Despite her limitations, and despite the fact that she functioned below he peers, Kaitlyn was accepted by the other children and participated in all school activities, including Christmas parades, and the overnight field trip. The school crossing guard provided her with part-time support in the classroom, primarily keeping her on task and helping her join in as much as was possible. Essentially, school provided a wonderful social experience for Kaitlyn, but cognitively and academically she was going nowhere. However, she was mainstreamed from the very beginning and I credit that as being one of the main contributing factors for her success today. Kaitlyn not only fits in, she is welcome in the “typical” world.

But not everything I did brought effective outcomes. Kaitlyn had a pretty severe case of strabismus, her eyes crossed, which was surgically “repaired” when she was six. I say “repaired” because although she had the procedure, it just changed and compounded her issues, it didn’t “fix” them. To this day we are still trying to correct the problems that were made even more difficult by the surgery. Today I regret having the procedure done-just another example of my ignorance prior to discovering Bob Doman and NACD.

One of the more significant contributions to Kaitlyn’s development was the use of growth hormones. Kaitlyn was so small and cute that people always wanted to pick her up, to hold her, and to treat her like a baby. I knew that if Kaitlyn were to progress beyond her diagnosis, she needed to be treated like a typical child at her correct chronological age. I began exploring growth hormones, but was unable to obtain them for her in Scotland. When Kaitlyn was about eight we moved to the United States, and I continued researching growth hormones and looking for a doctor who would consider prescribing them for her. In due course, I found a pediatric endocrinologist who was willing to work with us. Although Kaitlyn’s blood tests revealed that she was on the lower end of normal, her hand x-ray, measuring bone age, indicated she was growing quite a bit behind her chronological age.

Kaitlyn started the growth hormone shots when she was 9 and continued to use them until about 15, when her growth plates closed. She gained about 5 inches over what was her projected height and is now barely under 5 feet tall. This may not seem like a significant difference, but 5 inches really are a big deal to someone who is so short to begin with. Before she started the GH therapy, Kaitlyn was getting the typical Down syndrome shape; with the growth hormones she stretched out. She was able to wear more age-appropriate clothing, which in turn helped change others’ perceptions and, more importantly, their expectations of her. Additionally, her muscle tone improved, allowing her to climb a ladder, to go up and down a slide, and generally to interact with other children. Improved muscle tone also led to a more normal gait.

Meanwhile, Kaitlyn continued to attend school with typical classmates. At my request, she was placed in an optional multi-age typical classroom. This was helpful because it was just like a home with children of different ages and different levels of function, which is much more “normal” than the narrow competition of a regular classroom. Occasionally there were hiccups, such as when she didn’t want to sit down when she was supposed to or when she pulled other children by the arm, trying to catch their attention since she didn’t speak clearly. During the end-of year IEP meeting, I requested an additional year in a mainstream classroom, but this time the school refused to comply. At the time I felt that this was a terrible and unfair decision; but it turned out it was actually a blessing in disguise, because this pushed me to look for something else, something outside of the “system,” something that changed the course of our lives, The National Association for Child Development (NACD).

In IEP meetings parents are told that their child “can’t” do this and “can’t” do that. “She won’t amount to much because of her diagnosis,” is effectively the message. At an NACD conference I attended it became clear to me that our children can do so much more than the school system thought, than the world thought; that the key words to higher achievement for all of our children are expectation and opportunity. The turning point in Kaitlyn’s development was when I found my voice to express my higher expectations for her. Until then I felt that I was responsible for her development and education; with NACD’s guidance, I knew exactly what I should do. I was empowered and I had the guidance and support that I needed.

By the time Kaitlyn was 10, I had taken control of her development and education. I had taken her out of school to get a running start at changing her brain, at developing her cognition, at teaching her to think and communicate--to unlock her potential. Kaitlyn had two younger sisters who also needed my attention and care. So after we had things off and running, we did our NACD program and academics in the morning when we were both at our best, and she went to public school in the afternoons for music, art, and physical education—in a typical classroom, that was important. That worked really well and she grew developmentally, cognitively, and academically at an accelerated rate: she was catching up! But when time came for junior high, the question of Kaitlyn’s placement arose again. The principal of the elementary school tried hard to discourage me from mainstreaming her in junior high and insisted she needed to be placed in a special education classroom.

I wouldn’t budge. I visited the special education classroom at the junior high and observed the “teaching.” I noticed that the same social studies textbook was being used in 6th, 7th, and 8th grade and asked the teacher about it. She replied to me that yes, they used the same materials in all grades because the kids aren’t learning anything anyway. It was really “pretend” education. Thanks to NACD, I knew better. I knew that it was more beneficial for my daughter to receive more and more input. We weren’t going to get more out by putting less in. I had also learned from NACD that the more specific the input was for Kaitlyn, the more she was going to learn and retain.

I wouldn’t budge. I visited the special education classroom at the junior high and observed the “teaching.” I noticed that the same social studies textbook was being used in 6th, 7th, and 8th grade and asked the teacher about it. She replied to me that yes, they used the same materials in all grades because the kids aren’t learning anything anyway. It was really “pretend” education. Thanks to NACD, I knew better. I knew that it was more beneficial for my daughter to receive more and more input. We weren’t going to get more out by putting less in. I had also learned from NACD that the more specific the input was for Kaitlyn, the more she was going to learn and retain.

Kaitlyn didn’t go to that junior high, but instead attended a mainstream classroom at a charter school. I continued to advocate for my daughter all throughout junior and senior high school. Initially, the IEP team refused to allow part-time enrollment—they were concerned about testing her on subjects she wouldn’t take at school. I knew that the state law was on our side and the abbreviated day was possible, as long as it was written in the child’s IEP. I hired a lawyer. He came to the IEP meeting, but didn’t have to say a word, and the district agreed to part-time enrollment. We continued implementing the NACD program at home in the mornings, and at school Kaitlyn took Spanish, music, and other primarily non-academic classes.

I sometimes wish we had pursued a high school diploma, just for bragging rights, but doing so would have taken too much time away from her NACD program and real education. Instead of a piece of paper of questionable value, she developed neurodevelopmentally, gained an education--an academic, social, cultural, and functional personal education. She has grown from a child with very serious delays to a capable and competent young woman who is independent, has her driving permit and is working to get her license, makes her own doctor’s appointments, keeps an active social life with typical and special needs friends, and has great joy and fulfillment in public speaking.

Before starting the NACD program at the age of ten, Kaitlyn recognized a few words, in essence reading at a pre-first grade level. Now she reads at the level of most high school graduates and actually reads substantially more than most adults. She enjoys classics, adult novels, reading about the news, and even researches medical topics on the Internet. Initially, prior to starting her NACD program, her speech was very poor, communicating in single words and occasionally in couplets. Now, while her clarity isn’t perfect, she delivers detailed presentations on how swimming can enrich the lives of people with special needs. When she first began speaking publicly, I assisted her by helping her write the speech and she read it from her iPad. Now she speaks from notes and can confidently add or subtract from her address to suit her audience. And she is becoming more and more confident with each lecture.

Swimming has been a really big part of Kaitlyn’s life. She started swimming at ten, actually more like just floating in the water and holding her breath, but didn’t really know how to swim. Kaitlyn and her sisters joined a summer swim team and the coaches helped all three girls become confident in the water. Two years into NACD, at 12 she joined an all-year swim league and began intensive daily training. Unlike soccer, where she couldn’t keep up with the other children, swimming is a sport that allows her to be part of the team, yet compete against her own time. Kaitlyn happily swims for Aiken Augusta Swim League, USC Aiken Swim Club, and the Special Olympics where she always wins gold medals. Now that adults with intellectual disabilities will be allowed to compete in the Paralympics, Kaitlyn is determined to participate in that as well. Swimming has been a great social outlet for her; the various opportunities afforded her through the swimming groups have significantly helped her develop independence and maturity. She typically gets dropped off for her training sessions and calls when finished to get picked up, functioning as do her typical friends. After a very shaky beginning with her gross motor skills, Kaitlyn is now a very adept swimmer and is not only extremely physically fit, but also has a cute figure.

Because Kaitlyn has always lived in the typical world and has been expected to behave properly, her behavior is more appropriate than most young adults. She has also always sought opportunities to do “normal” things. In high school she decided on her own she wasn’t going to sit at the special needs table and instead sat with “normal” kids. She persisted, and with time she made good friends with typical kids who remain her friends today. Everywhere Kaitlyn goes she is warmly greeted as a friend by many young adults in the community.

Another example of her determination was finding a date for the senior prom. Kaitlyn came to me before the prom and told me she wanted to ask one of her “typical” friends to the prom. I didn’t know how to respond and called Bob at NACD and we discussed it. We decided that she had a very healthy understanding of who she was and could give many of us lessons to help us put it all in perspective. If that was her choice, then she should have the chance, even if it meant possible rejection and disappointment. She didn’t get started asking until right before the prom and asked a couple of typical boys who already had dates. Kaitlyn wanted to go to the prom so badly, she just didn’t want to go with one of her special needs friends, who I’m sure would have gladly accepted her invitation. I have never really known why going to the prom with a typical boy was so important to her; she had gone to dances and even an ROTC Ball with one of her special friends before and had had a wonderful time; but I needed to honor her wishes. In the end, Kaitlyn decided to invite a typical boy from swim team. He already had a date, but kindly accepted the invitation anyway and had two dates! That was an exciting night for Kaitlyn.

Another example of her determination was finding a date for the senior prom. Kaitlyn came to me before the prom and told me she wanted to ask one of her “typical” friends to the prom. I didn’t know how to respond and called Bob at NACD and we discussed it. We decided that she had a very healthy understanding of who she was and could give many of us lessons to help us put it all in perspective. If that was her choice, then she should have the chance, even if it meant possible rejection and disappointment. She didn’t get started asking until right before the prom and asked a couple of typical boys who already had dates. Kaitlyn wanted to go to the prom so badly, she just didn’t want to go with one of her special needs friends, who I’m sure would have gladly accepted her invitation. I have never really known why going to the prom with a typical boy was so important to her; she had gone to dances and even an ROTC Ball with one of her special friends before and had had a wonderful time; but I needed to honor her wishes. In the end, Kaitlyn decided to invite a typical boy from swim team. He already had a date, but kindly accepted the invitation anyway and had two dates! That was an exciting night for Kaitlyn.

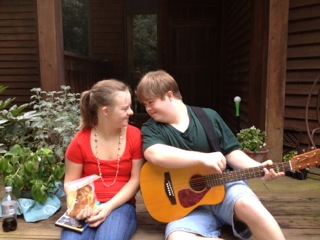

Since then Kaitlyn has developed a close relationship with her boyfriend. Nathan, a young man with Down syndrome who is also an NACD kid, is very kind to her and they deeply care for each other. He lives just 30 minutes away from our house, and they see each other frequently. They go to dinner, to movies, and hang out at each other’s homes and do program together on Tuesdays and Thursdays. They already talk about getting married, but recognize that more pieces of their respective puzzles need to come together before they could do that.

As an ambitious young woman, Kaitlyn is working hard to continue her growth. She is exploring options, including having her own business, and she is passionate about working with and helping children. Kaitlyn has a lot to offer and a lot to give. She has lessons that she can teach us all.

At 23, are we stopping program? Absolutely not!

To be continued.